Padding is to saddle fit as socks are to shoes. It is an integral part of the fitting dynamic. Unfortunately it is all too often ignored when a saddle or tree is being selected to fit a particular horse. Padding impacts all three dimensions of fit: width, arch and angle.

One of the first attempted solutions to a saddle fit problem is padding, specifically more padding, but as we shall see, this often exacerbates the problem. Let’s examine closely what padding does to fit by first looking at its impact on width.

When the saddle is completed, the load bearing member, or bars, are usually covered with fleece which makes any detailed visual examination of the contact and voids under the bars difficult. It is therefore logical and a long-established tradition in custom saddle making to select a tree to fit a particular horse prior to the construction of a saddle.

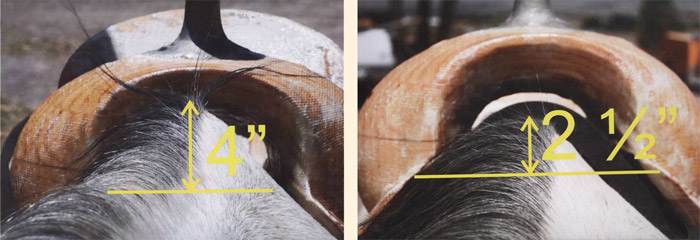

When the custom saddle arrives, the new owner typically uses the standard blanket and pad or one of the new, thick, high-tech pads filled with air, gel or memory foam. Unfortunately the saddle no longer fits where the bare tree did on the horse’s back. Let’s assume for a moment that the total net compressed thickness of the padding under the saddle is one inch. Looking at Figure A, we see that 1′ measured horizontally at a 45 degree angle (the angle of the front shoulder of an average horse) measures 1-1/2″ times two (each side), now making the width where the bare tree was set 3 inches wider. Measuring the rise of 1″ of padding, measured in a vertical axis through a 45 degree angle is again 1-1/2″ and we see that the original width of the gullet (6-1/2″) now sits much higher on the horse. The point measuring 6-1/2″ accommodating the gullet of the tree now sits 1-1/2″ higher in front, changing the point of contact and pressure distribution significantly.

Now let’s look at the rise in the rear. Measuring the vertical rise created by the addition of 1″ of padding under the bars (which are now angled at 22 degrees on most trees), we see the rise created by the padding is 1-1/8″. A quick calculation shows that the padding raised 3/8″ more in the front shoulder area than in the rear loin area, caused by the different angles of the horse’s body covered by the pad. When you raise the front 3/8″ more than you raise the rear, this causes the middle to be raised completely off the horse’s back, a condition known as “bridging”. Without this contact and support in the middle, pressure is concentrated where contact remains and unfortunately, this condition lies hidden under layers of padding and obscured by fleece. We are left with only the behavior cues and ultimately white hairs, together with other telltale remnants of damaged tissue and soreness to discover the problem.

Now turn our attention back to Figure B and look at the contact of the bars against the shoulder as compared to Figure A. The rise from padding has also created another problem. The slope of the shoulder here is not uniform as it was in Figure A. The shoulder is rounding off as the tree has risen and now the contact is on the lower part of the bar. Again, reduced contact means increased pressure where contact remains. Angle is now affected since the angle where the bare tree contacted the horse is no longer the same as the angle where the saddle with padding now sits.

Padding is not inherently bad; it cushions the back and helps it “breath”, letting moisture and heat dissipate, but it is essential that the padding to be used with the saddle tree is taken into account to maintain proper fit.

English saddles and some new western type saddles have approached this differently by building the padding into the basic saddle. A relatively thin pad is used under this type of saddle which does not distort the fit and serves to keep sweat from direct contact with the saddle without distorting the size and shape of the fit. Since the tree , with its built-in padding, is not covered by camouflaging fleece as in traditional western saddles, a visual inspection of the fit is much more easily achieved. The surface of the flocked panels comprising most English saddles is very convex, or curved, and does not offer a wide enough area to distribute the weight of rider and saddle, nor low enough psi (pounds per square inch) to avoid compromised blood circulation to the cutaneous and subcutaneous layers of the horse’s back.

At Specialized Saddles we have solved these problems by utilizing a system which provides a larger surface area, with the visibility of fit and built-in padding offered by an English type saddle. This is done using a patented, easy to use, adjustable fit system.

For saddle padding to be effective at one of its primary functions, that of letting the back “breath”, it must have a porous surface so air can circulate. If the pad is dirty and debris is allowed to clog the surface of the pad heat and moisture will be trapped. Regular cleaning of pads is important. Failure to do so can lead to skin problems and back problems from accumulation of heat.

Another dilemma is that open cell foams used in some pads, while allowing more surface air flow, also allow moisture and bacteria to wick into, and contaminate the pad. Closed cell foams do not have the surface air spaces ad tend to trap heat more than other more porous materials. Course weave mohair blankets and/or natural fleece provide a time proven surface that allows moisture and heat dissipation, but remember the thickness must be taken into account. Some new padding materials like those offered by Supracore or Dixie Midnight also provide for increased air circulation.

Remember to allow width for whatever padding you use when selecting (or adjusting) a saddle. Padding is an important element of saddle fit and is all too often ignored when saddle fit considerations are being made.